History

The chronicle of Gaineswood National Historic Landmark is complex. It begins at a time in American history when Native Americans in the Southeast were being displaced, when African American men, women, and children were enslaved, and the plantation system was becoming the backbone of the southern economy.

The grounds and historic home weave a narrative reflective of the intricate, longstanding, and multifaceted evolution of the Black Belt Region and its role in Alabama history.

Early Days

In 1821 George Strother Gaines, an Indian agent for the United States government, came to the Demopolis area and built a home. Gaines’ double pen dog-trot cabin was a common style of frontier home. The cabin had two rooms or “pens” connected by a breezeway with a common roof and floor.

While in the area, Gaines played a prominent role in Alabama history. He negotiated treaties with Chief Push-ma-ta-ha, also known as the “Indian General”, who was a highly regarded regional chief of a major division of the Choctaw nation.

In the fall of 1834 Nathan Bryan Whitfield moved his family from North Carolina to a plantation of 5,000 plus acres, 15 miles south of Demopolis.

Making of a Home

After losing three children to a yellow fever epidemic, Nathan Bryan Whitfield purchased the Gaines’ property and brought his family to the area in February, 1843. The members of the family included their five surviving children, six orphans of their cousins. Whitfield’s wife, Betsey, was expecting their 12th child.

To ease the overcrowding, Whitfield sent the six oldest children to boarding schools and then began building additions to the home. He added the parlor, center hall, and two-thirds of the dining room, and created two upstairs bedrooms over the cabin. Whitfield was his own architect and designer and, at times, builder. It took eighteen years to complete the mansion.

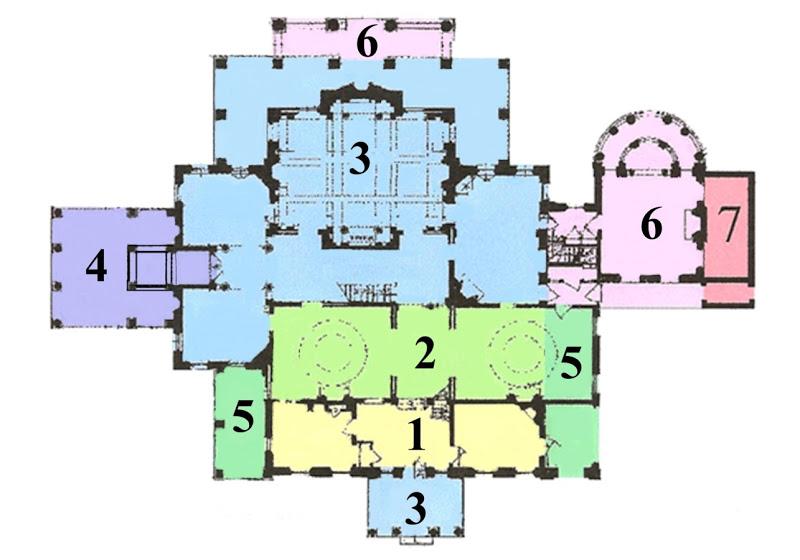

Dates of Additions to the Home:

Section 1 1821-1843

Sections 2 1843-1847

Sections 3, 4 1847-1855

Section 5 1856

Section 6 1860

Section 7 1861

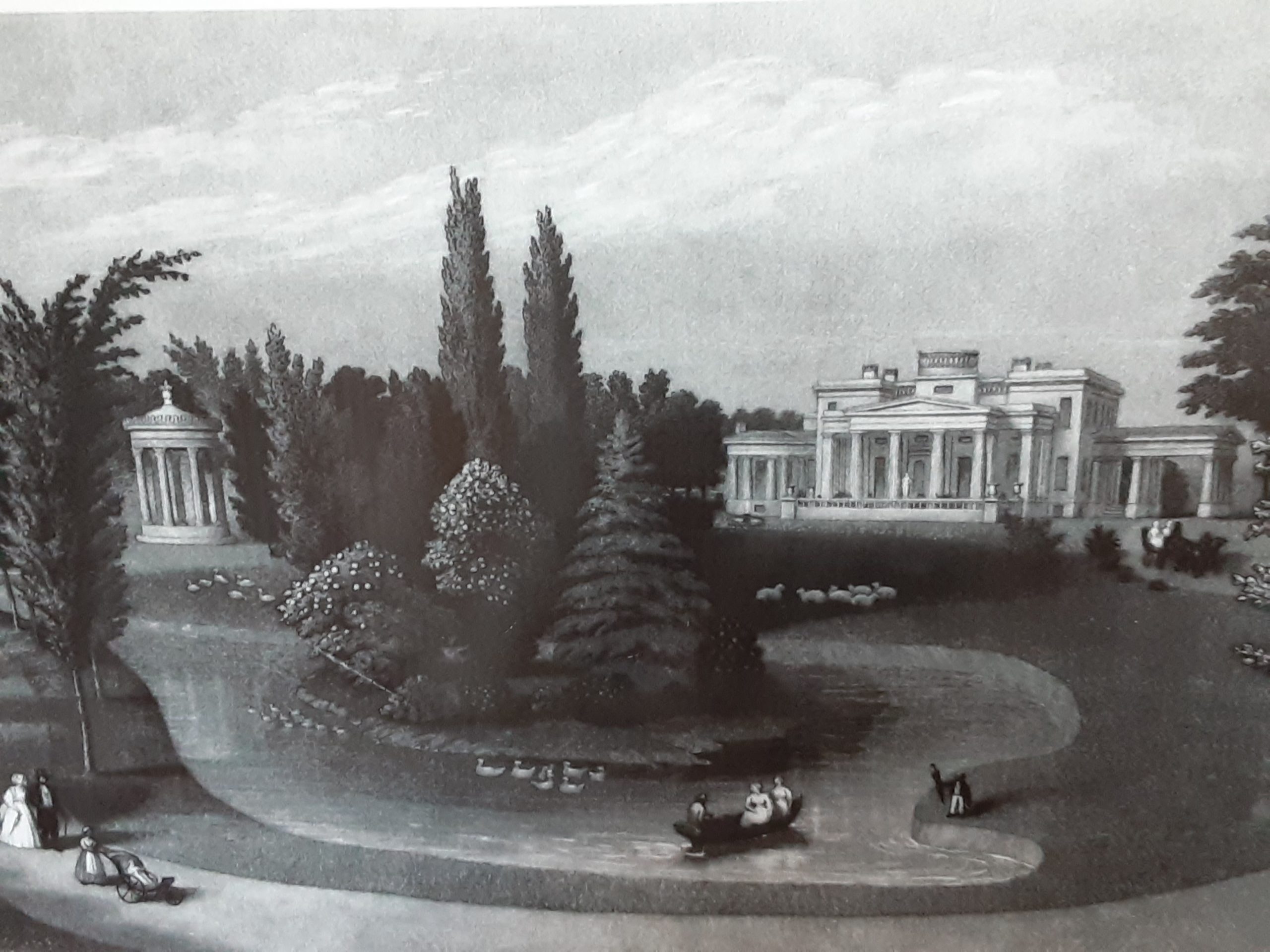

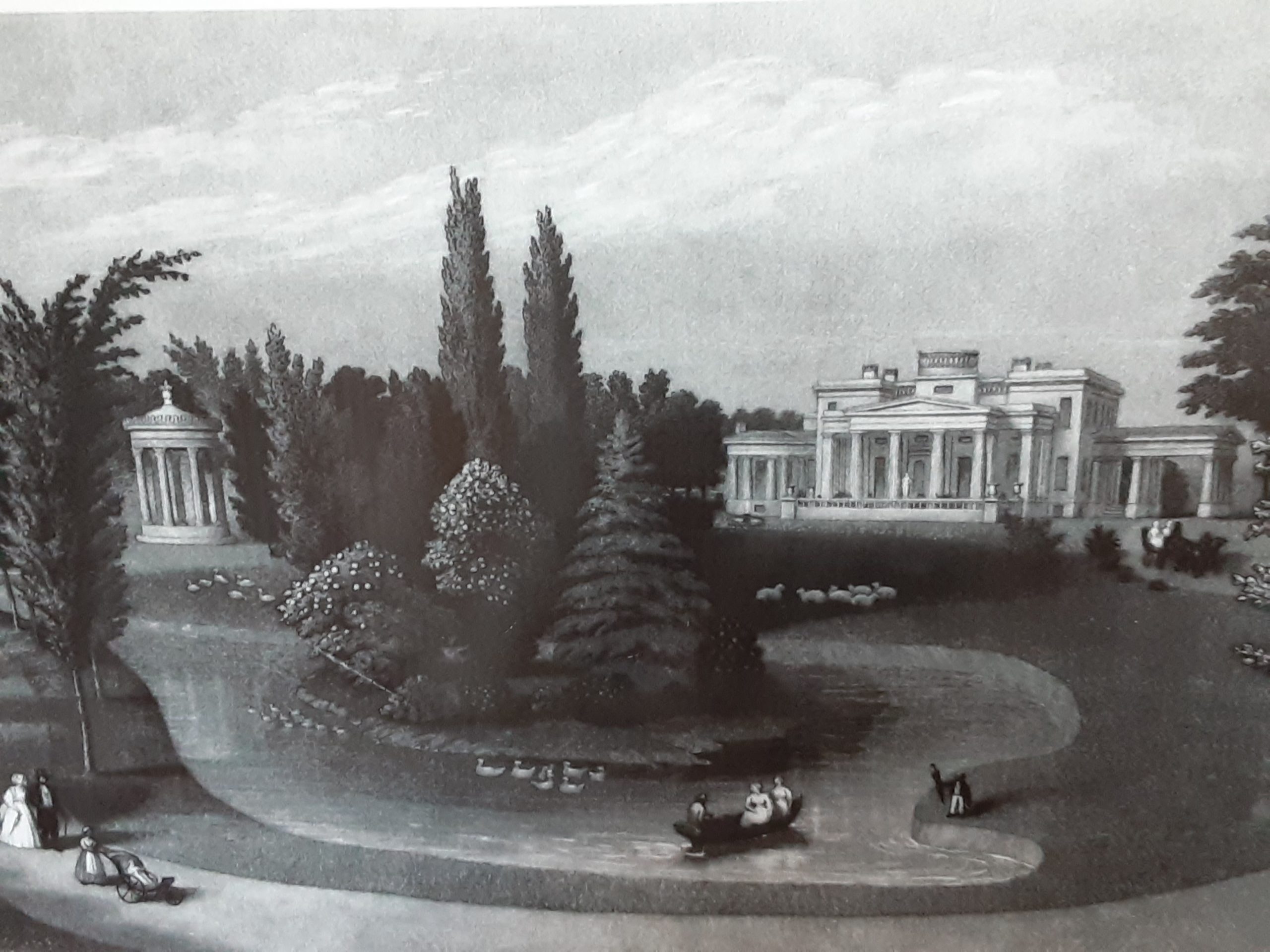

In 1860, John Sartain, of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, was commissioned to do a steel engraving of Gaineswood from a photograph taken by Chauncey Barnes of Mobile.

Diagram of new additions by Whitfield, starting 1843.

Saratain’s steel engraving of Gaineswood, 1860.

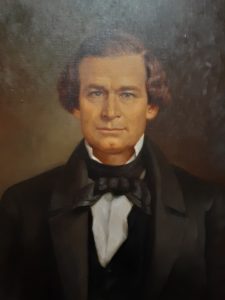

Nathan Bryan Whitfield

Betsey Whitfield

Bettie Whitfield

Bryan Watkins Whitfield

Nathan Bryan Whitfield

The Whitfield Family

Nathan Bryan Whitfield (1799-1868) was born in Lenore County, North Carolina in 1799. He was educated at the University of North Carolina and later served in the state legislature. In 1819, he married his first cousin, Elizabeth (Betsey) Whitfield. After searching the southeast for fertile and inexpensive farmland, he decided to purchase land in Alabama. He moved his family to the area in 1834. Tragedy stuck in 1842 in the form of a yellow fever epidemic that took the lives of three of the Whitfield children. Searching for a healthier environment, he purchased property near Demopolis, Alabama, from George Strother Gaines and moved the family into the small dog-trot cabin in 1843.

Elizabeth (Betsey) Whitfield (1801-1846) and Nathan Bryan Whitfield had twelve children. Betsey dedicated herself to raising her family and running the plantation home. She saw the completion of the dining room and parlor before she died in 1846 at the age of 45 of a digestive illness. Much of the house was completed while Whitfield was a widower.

A man of many talents, Nathan Bryan Whitfield acted as architect, designer and builder for his home. The inspiration for his estate came from Greek Revival structures surrounding him, his extensive travels, and his personal library including architectural pattern books. In his own way, Whitfield assembled popular Greek Revival stylistic elements into an interesting, unexpected, yet coherent structure. This architectural jewel evolved from artistic vision and real need of its creator into what many call one of the finest examples of the Greek Revival style in the United States

Gaineswood’s distinctive architecture is the reason for its designation as a National Historic Landmark.

In 1857, Whitfield married Elizabeth (Bettie) Whitfield. Nathan and Bettie had one daughter.

Bryan Watkins Whitfield (1828-1908) was a son of Nathan and Betsey. He was a physician and served as a surgeon for the Confederacy during the Civil War. After the war, Bryan practiced medicine in the Demopolis area. He and his wife, Mary Alice Foscue Whitfield, purchased Gaineswood from his father in 1866.

Contributions of Enslaved Workers

The majority of skilled laborers who built Gaineswood were enslaved. Many of these names are lost to history, but we do know that a man named Dick was a mason and master builder. Another man, Sandy, was also a mason, and James was a 24 year old carpenter.

We know of a very special man named Isaac. N. B. Whitfield travelled extensively, and Isaac apparently traveled with him. They were exposed to many dangers and illnesses, so in 1825 he and Isaac were vaccinated for smallpox. A letter dated 1847 possibly the same Isaac working on the columns for the house.

Other enslaved persons became domestic servants and were tasked with household chores. A few of these jobs included cooks, butlers, carriage drivers, gardeners, maids, nurse maids, laundresses, seamstresses, and valets. From documentation we know some of their names: Phoebe, a weaver in 1835, and Hannah and Bethemin who were cooks.

By 1861, Gaineswood was the center of a large plantation where cotton was the major crop harvested and tended by many enslaved field hands.

Postbellum

In 1866, Nathan Bryan Whitfield became gravely ill and his son, Dr. Bryan Watkins Whitfield purchased Gaineswood from him. The family moved into the home on Christmas Eve of that year.

Edith James Whitfield Dustan bought the home from her brother in 1896. She made improvements and moved the kitchen to the basement.

The Dustan sisters sold the house to the Kirven family in 1923, thus ending the Whitfield ownership.

Gaineswood remained a private residence or vacant throughout the years. Many families have called this place home since 1923 and Gaineswood has benefited from their care.

In 1966, the state of Alabama purchased the home. Ownership was transferred to the Alabama Historical Commission in 1971. After extensive restorations, Gaineswood was opened as a house museum in 1975.

Tidbits

Margaret McLure’s Story

Margaret McLure was a confederate sympathizer in St. Louis in 1863. The Union army accused her of smuggling Confederate mail, seized her property, imprisoned her and eventually exiled her from the state of Missouri to Mississippi. Hearing that Missouri soldiers were paroled from the fall of Vicksburg to Demopolis, she wrote to a family friend, Lieutenant Hall, and asked for help. He went to Mississippi, picked her up, and brought her to the camp at Demopolis. Lt. Hall searched to find respectable lodging for Mrs. McLure, and a visit with Bettie Whitfield provided just that. Mrs. McLure resided with the Whitfields for the next two years. After the war ended, Mrs. McLure returned home and became the founding President of the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

Engineer’s Surveying Transit

The faceplate reads: “Manufactured Expressly for Capt. A. P. French C. E. Demopolis Ala. By Stackpole & Brother New York 886”. The instrument has no springs, as found in more modern instruments. Instead, opposing brass screws are employed to obtain micrometer adjustments. The cross hairs were periodically replaced with a strand of the web of a certain species of garden spider and attached to the reticule of the instrument with tiny spots of glue.

Tradition has it that this engineer’s surveying transit was left at Gaineswood in payment of a debt, presumable about the time of the War Between the States.

The transit was used by Jesse George Whitfield, Civil Engineer, grandson of Nathan Bryan Whitfield. J G Whitfield made the official map of the City of Demopolis and did most of the land surveying and map making in this area during his long career.

The transit was loaned to Gaineswood in 1981 by N B Whitfield’s Grandson, Thomas H. Whitfield a Civil Engineer.

Painting of the

“Burning of the Eliza Battle”

Nathan Bryan Whitfield painted this steamship accident on the Tombigbee River 1858. This event has been flavorfully told by Kathryn Tucker Windham and Margaret Gillis Figh in “13 Alabama Ghosts AND JEFFERY.”

Portrait of Edith Winifred

A portrait of one of the Whitfield daughters, Edith Winifred, hangs above the piano in the parlor. This young girl was ten years old when she died of yellow fever, the third child that the family lost during an epidemic. General Whitfield painted her portrait ten years later from memory.

Epernge

In the center of the dining table at Gaineswood there stands a beautiful epergne. The word “epergne” is derived from a French word meaning “save” or “conserve”, and an epergne is designed to be a decorative and functional piece that saves space on the dining table. It holds candles aloft to illuminate the table while serving as a lovely centerpiece. Epergnes had bowls or baskets around the central column. The bowls were meant to hold fruits, nuts, and other food items. Most epergnes also included flower vases. Some elaborate epergnes might feature a central tureen or condiment holder like salts, cruets, or spice boxes. General Whitfield designed this particularly beautiful epergne featuring Greek maidens for his home.

Sartain Print

In 1860, Mobile photographer Chauncey Barnes took a photograph of Gaineswood. The photo was sent to John Sartain in Philadelphia the premier engraver on steel in America. He created engraving plates from the photograph. The image shows Gaineswood at its finest, its landscaped grounds, members of the Whitfield family and enslaved people.

Address

P. O. Box 443

805 South Cedar Ave.

Demopolis, Alabama 36732

Admission

$10 Adults

$9 Seniors

$8 College and

Military

$5 Students 6-18

Group rates are available for 10 or more. Call us at (334) 289-4846 for more information or to make an appointment.

Blue Star Museum: We proudly offer free admission to any active duty military personnel and their families between Memorial Day and Labor Day.

Hours

Open: 10 a.m. - 4 p.m.

Tuesday - Saturday

Closed: Sunday and Monday, unless by special appointment. Call us at (334) 289-4846.

Other large group tour times are available by appointment.

Visit other historic Alabama sites by clicking below!